What We Learned from the Court Case: Inclusive Wayfinding Beyond Compliance

- Humanics Collective

- Jun 16, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2025

The Sunshine Coast University Hospital ruling and its impact on inclusive wayfinding

In 2021, the Federal Circuit Court ruled that the design and construction of the Sunshine Coast University Hospital (SCUH) indirectly discriminated against people with vision impairments. The plaintiff, Peter Ryan, who was legally blind, successfully argued that the hospital’s built environment imposed conditions he could not reasonably meet, in breach of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) ([Ryan v SCHHS 2021] FCCA 1537).

The case in brief

Ryan, who used a wheelchair and cane, and could read Braille, argued that the hospital failed to provide an environment he could safely and independently navigate. The court found that:

Entry paths lacked tactile cues and sufficient contrast to allow unaided navigation.

Wayfinding signage was missing or non-compliant, particularly in key areas like lift lobbies.

The overall system failed to function for users with vision impairments.

Justice Jarrett concluded that SCUH required Ryan to meet a “condition or requirement” he could not reasonably satisfy. This, by law, constituted indirect discrimination.

Our role—and our view

Humanics Collective was engaged to support the hospital in improving compliance after the ruling. While we respected the court’s decision and engaged fully with the process, we don’t fully agree with its interpretation of what constitutes functional accessibility in a complex environment (see return brief, p.6). In our experience, meeting standards doesn’t always guarantee usability, and equity isn’t always achieved through uniformity.

Listening to users—really listening

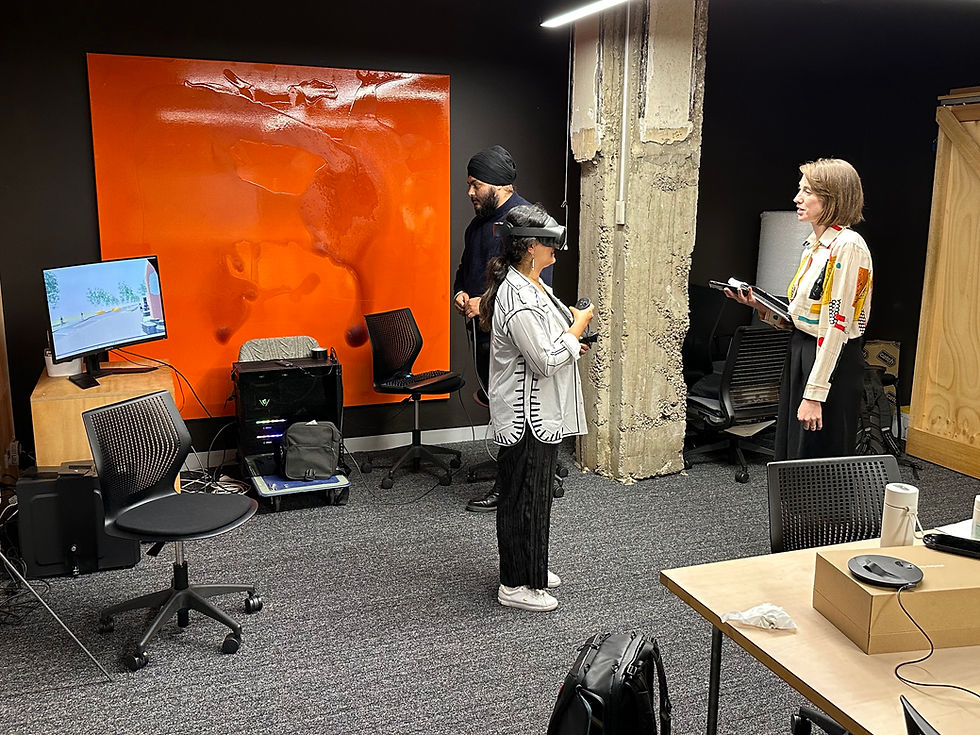

Rather than defaulting to a standardised solution, we proposed a comprehensive engagement program with people who had different types and degrees of vision impairment (VIPs), as well as sighted users; staff, volunteers, and patients.

What we heard was consistent: there is no single ‘VIP experience’. Some people rely on tactile signs, others on a white cane, others on audio support. Tools and preferences vary widely. A common thread from our VIP participants was that full independence, at all times, is an unrealistic expectation, particularly on a first visit to a large, unfamiliar hospital.

And that’s not a concession. It’s a practical truth. Framing accessibility as an all-or-nothing issue risks pushing the conversation toward unrealistic demands. And when the ask becomes too far removed from reality, people stop listening and stop engaging.

Redefining 'replacement'

One key point of contention in the ruling was the interpretation of “replace.” We argued that replacement shouldn’t mean reinstalling flawed signage in the same location, but improving usability through better placement, higher contrast, and greater visibility. The goal isn’t just to tick a box, it’s to help real people find their way.

So what should we be doing?

The answer isn’t more signage. It’s smarter support:

Train volunteers and front-of-house staff to guide and assist VIPs clearly and confidently, both verbally and physically.

Provide meaningful pre-visit information, especially for users arriving by public transport or taxi, who are more likely to travel without support.

Offer orientation or induction sessions for regular VIP visitors. Help them get familiar with the layout, the placement of RBT signage, and the system logic.

Use systems consistently. Consistency builds trust, confidence, and spatial memory.

We tested our proposed solutions extensively on site, with the same groups of users. The feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Many participants said the changes made the space finally feel navigable and supportive. That revised system is now being implemented and is set to be in place by the end of the year.

What this means for your project

This case shows why accessibility needs to go beyond compliance. It needs to be functional, realistic, and grounded in the experience of real users. It needs to reflect human diversity, not just human rights.

The best way to get it right?

Don’t guess. Ask. Then test, improve, and keep asking.